Relativism and Theoretical Kinds Perspectivism

_____________________________________________

A synthesis drawing on Kane Finlay Baker’s Thesis

As it turns out, many people find the idea of truth being relative obviously and dastardly wrong and find other theories of truth (like correspondence) to be obviously true. I’m going to be the voice of the contrarian and show why this line of thought is mistaken and defend global relativism (all truth is relative). This will be a more extensive version of the previous defense made.

Table of Contents

What Relativism is NOT:

Before we actually speak of relativism, from my experience, it is more important that we talk about what relativism is not to avoid the common misunderstandings that seem to steer people away from the position.

To start, relativism is NOT subjectivism. Relativism by itself does not entail that believing that P means that P is true and it also does NOT entail a thesis of plentitude that for any proposition P, there is a stance in which P is assigned any truth value. (Different relativists may say different things about this point).

This is one that is repeated over and over again but is understandable given some notions of relativism that people are familiar with (e.g. Cultural relativism, agent-relativism). Alas it is still wrong and not what relativism is

Relativism is NOT the view that all views are equal nor is this a direct entailment of relativism

We’ll develop the thesis of relativism largely through Kane Baker’s work and scientific perspectivism

Perspectivism and Relativism

Before we define relativism we will actually take a look at perspectivism, trust me, it will make relativism much more intuitive instead of presenting it to you prima facie as relativism is a novel idea and the standard human instinct is to reject that which seems to go against our common, we will define relativism later down the road given this and start with scientific truths. Take note that perspectivism is not about which propositions are true, but rather about the model-world relation itself; it re-evaluates what it means for a scientific model or claim to be true of the world (The truth of propositions would be the job of relativism to explore). According to perspectivism scientific claims must be conditional on a perspective.

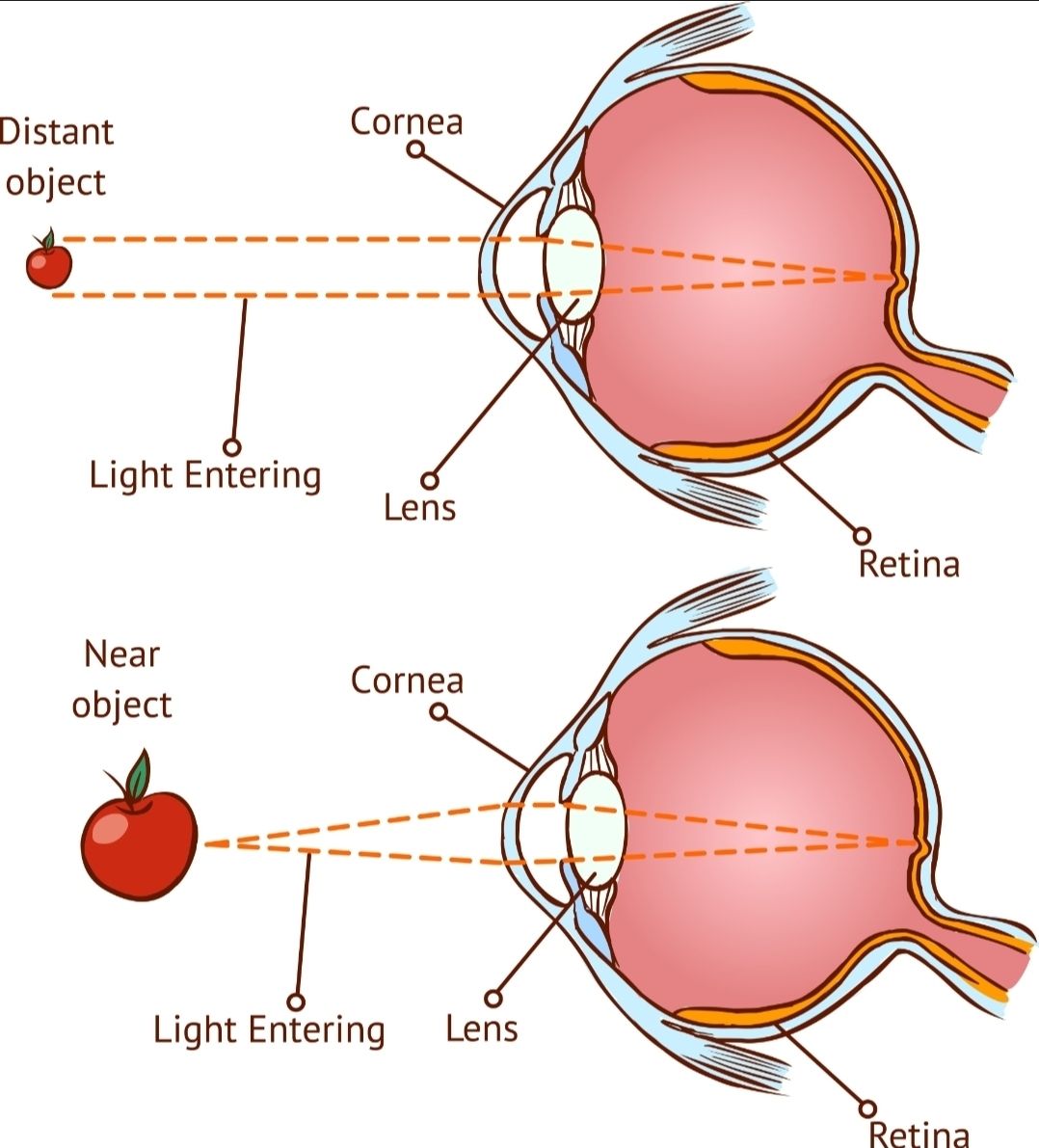

An exemplar for this perspectival model-world relation is human color vision. Color perspectivism henceforth serves as a guiding analogy for scientific perspectivism. Color is not an objective property of the world but the product of an interaction between aspects of the environment (like surface reflectance) and the evolved human visual system.

This gives us features that define a perspectivist position:

(1) Facts (like color) are interactional products. We do not see the world as it is; we see it from a colored perspective. Similarly, scientific claims are always made from a theoretical perspective;

(2) Claims made within a perspective can be true or false. "Grass is green" is a true statement for a normal human trichromat under normal conditions;

(3) Perspectival knowledge is not an illusion as it tracks the regularities. Trichromatic vision, for example, evolved because it successfully tracks the difference between ripe (red) fruit and (green) leaves, which is a “fact” about the world;

(4) Perspectives are inherently partial. The human visual system is only responsive to a tiny fraction of the electromagnetic spectrum. Likewise, scientific theories and models are selective, focusing only on specific features of a target system;

(5) Different perspectives are compatible;

(6) perspectives may be shaped by the needs and goals of their users e.g. Humans may have developed red-green discrimination to find fruit, bees developed UV sensitivity because it makes flowers (which have UV-reflective patterns) stand out.

We use color science (itself a perspective) to explain color vision. But what if we treat the claims of color science (its regularities about wavelengths, cone cells, and neural processing) as non-perspectival? If we do, then we have successfully "escaped" the seemingly perspectival fact ("the sky is blue") and reduced it to a set of non-perspectival facts (surface reflectance, atmospheric scattering, and the specific functioning of the human visual system). We will talk about this in depth.

Chakravartty makes this point using the example of viewing a person, Peter. From afar, Peter appears small; up close, he appears tall. These are perspectival appearances. But they are uncontroversial because they are underwritten by a set of non-perspectival facts: Peter's actual height, the laws of optics, and the facts of our visual apparatus.

This sort of objection is why the perspectivist, if they want to be a perspectivist, has to endorse a global perspectivism. This is where theoretical perspectivism arrives. The talk here, therefore, is not over the instruments themselves, but over the nature of the theories and models we use to build and interpret them. This will address the line of thought people like Chakravartty endorsed.

So, we have this theoretical perspectivism and it can be driven by a sort of "multiplicity intuition" whereby truth is revealed from multiple, different viewpoints.

Failure of Fit

But more importantly there is argument from incompatible models/Underdetermination. Whereby scientific practice is replete with multiple, often contradictory, models of the same target system. This occurs both synchronically (e.g., different models of fluid dynamics or nuclear structure used by contemporary scientists) and diachronically (e.g., successful past theories like Newtonian mechanics that are now considered false).

This stands contrary to the standard "success-to-truth rule" that undergirds scientific realism. If success/working indicates truth, and we have multiple incompatible successful models, we are forced to conclude that the world itself is contradictory. Perspectivism would say the incompatibility is only apparent. The models are not absolutely true, just as "Frank is to the left of Vincent" and "Frank is to the right of Vincent" can both be true, provided they are indexed to different perspectives.

This is where alethic relativism (the view that truth itself is relative to a perspective.) comes in as the “form” of perspectivism to back up what is being said here

So, per Natalie Ashton we have the three theses:

Dependence (D): Beliefs have truth-values only relative to perspectives.

Plurality (P): There are many perspectives.

Non-Neutral Symmetry (NNS): There is no perspective-independent way to judge between perspectives.

To quickly go through the thesis (which will be developed further in this article):

The dependence (D) clause is simply stating that you can assign truth value to a belief only from a given perspective (or framework, scheme, standpoint, etc). So the truth of propositions is relative to perspectives and there are no truths simpliciter, i.e. no truth-values independent of all frameworks. Now note that NNS is not equal validity, which is a ranking of perspectives (ranking them as equal). NNS on the other hand is saying there is no neutral way to privilege certain perspectives above others, such that whenever you judge/assign truth-value to a perspective, you do so from within a given perspective

No Neutrality As far as NNS goes, it actually seems rather intuitive that it is impossible to find a truly neutral or objective standard or some sort of meta-justification/meta-truth assignment to judge between systems of belief. Any justification and truth-value you offer for your own system will necessarily start from principles and assumptions within that system. (See the SEP entry on relativism and No Neutral Ground)

(Do note that “perspective” is meant to be a broad catch-all term here and it can be replaced with things like framework, schemes, paradigms, parameters, etc.)

the truth of any proposition according to the relativist is relative to some framework where a “framework” could mean (a) conceptual scheme, language, epistemic system, paradigm, parameters, belief system, etc etc. So we obtain

A proposition P is true relative to framework F if and only if P satisfies the truth-conditions recognized within F. (There are few different ways to say this and as said before different relativists will say different things about it)

Thus, there are no framework-independent/neutral (absolute) truths. Truth is indexed to systems of evaluation, etc. Relativism is saying that there are no truths that are just out there that start from nowhere.

This position, and only this one, genuinely saves the "success-to-truth" inference from the problem of incompatible models. It allows us to say that Newtonian mechanics was successful and was true (relative to the Newtonian perspective) and that General Relativity is successful and is true (relative to the Einsteinian perspective).

Now the argument from incompatible models alone is not enough to motivate relativism and that’s why the failure of the incompatible model’s argument motivates the introduction of a second, more fundamental, and far more powerful argument: the "Failure of Fit" argument.

This argument is going to come from Kuhn and TVAR, and so it’ll shift from models to the lexicons (classification schemes, conceptual frameworks) that underlie them.

The argument proceeds as follows:

All evaluation of truth can only be conducted within a lexicon that is already in place.

Standard realism requires that a true statement corresponds to the real world.

For this correspondence to be possible, the world itself must be "lexicon-dependent" it must possess its own intrinsic, objective conceptual structure, its own "language".

This idea of a "language of the world" is untenable

Human lexicons are contingent, constructed, evolving, and purpose-driven artifacts. It is "most unlikely" that our contingent human concepts would happen to "match" the one true, objective, lexicon of the world.

So, the problem is not just that many of our models are incompatible with each other, but that our entire system of representation is of a different kind than the world itself. Given this, I take it that it is plausible to claim we can block the "Escape from Perspective".

The "Escape" move always consists of appealing to a background theory (like optics or general relativity) as the non-perspectival ground. But the "Failure of Fit" argument applies to that theory as well. That background theory also uses a lexicon, a set of classifications and concepts, that is just as human-made and contingent as the one it was meant to ground.

This argument applies globally to observations, to instruments, to theories. It forces a dilemma: either (a) accept that all facts are perspectival (relative to a constructed lexicon), or (b) embrace a radical, global skepticism, since none of our representations can ever be said to "fit" the world.

Crucially, this argument is not about distortion. "Distortion" implies we have a non-distorted original to compare against. The "Failure of Fit" argument claims there is no original "language of the world" for our lexicons to either match or distort.

That aside, consider Putnam’s world with just three atoms (x1, x2, x3) as a thought experiment

How many objects are in this world?

From the perspective of Compositional Nihilism (CN), which denies parts compose objects, there are 3 objects (x1, x2, x3).

From the perspective of Unrestricted Composition (UC), which holds that any collection of objects composes a new object, there are 7 objects (x1, x2, x3, x1+x2, x1+x3, x2+x3, x1+x2+x3).

Both "3" and "7" are true statements, but their truth is constituted by the adoption of a specific (and optional) conceptual framework.

A standard “escape” here would be to say something to the effect that this is just a "verbal dispute" and that the real, perspective-independent fact is "there are three existent atoms". This move is highly intuitive and understandable but it is question-begging in that it assumes that the "atom" lexicon is the one true "language of the world" and the "object" lexicon is not. The "atom" description is just another perspective, not a "behind-the-schemes" ultimate reality.

In our complex world, unlike Putnam's simple one, this problem is magnified infinitely. The world's complexity forces scientists to select what to model based on changing research interests. What counts as the phenomenon to be explained (the explanandum) is a product of the perspective. For pre-Newtonian astronomers, the mass of the planets was not a relevant feature to be explained. For Aristotelians, the stability of orbits was not a problem to be solved, because their theory assumed it. Because our scientific questions (which are part of our perspectives) are themselves contingent and evolving, we can never form a complete "disjunction" of all possible valid frameworks. There is no static, non-perspectival "world" that we are all describing; there are only our perspectival representations of it.

Prebuttals

So, if, as the relativist argues, traditional realism requires an implausible "fit" between our contingent lexicons and a pre-structured, "lexicon-dependent" world, how might the realist respond? If they do decide to attack such a lexicon dependency? I’ll sketch out some “prebuttals”

1. The realist can argue that their commitment is not to truth, but to approximate truth. Perhaps approximate truth does not require a perfect fit between our lexicon and the world's lexicon.

R: This is a good response and what is to be expected intuitively speaking, as we don’t have to get the exact truth, but this fails because the concept of "approximate truth" is parasitic on the concept of "truth" anyway. To say a statement (e.g., "The distance is 3500 miles") is "approximately true" is to say it is "close to" an exactly true statement (e.g., "The distance is 3459 miles"). This simply pushes the "Failure of Fit" problem onto that new, more precise statement. The challenge of how it fits the world remains unsolved. Also, there are many other hard implications for such a view, for example why should we believe, that arguments should preserve truth given a view of approximate truth?.

2: What I take to be one of the most sophisticated realist responses. The "language of the world" is mathematics. E.g. Structural realism; scientific theories are mathematical structures, and they "fit" the world because the world itself instantiates an isomorphic (or partially isomorphic) mathematical structure.

R: There are three good reasons to think this false however, the first being it assumes a highly controversial Platonist ontology of mathematics, where abstract mathematical objects somehow exist and are "instantiated" by physical systems. The second, is that, a mathematical structure, being purely abstract, says nothing about the physical world on its own. To apply mathematics, one must first use a non-mathematical, natural-language lexicon to carve up the world into objects, properties, and relations (e.g., "this is a population," "these are organisms," "this is the 'parent-of' relation"). Only after this "structure-generating description" is in place can one abstract a mathematical structure from the description. Therefore, mathematization does not solve the "Failure of Fit" problem; it presupposes that our natural language lexicon has already successfully "fit" the world. The original problem remains entirely untouched. And in scientific practice, mathematical structures do not map onto the world; they map onto highly idealized models (e.g., frictionless planes, point masses, ideal gases) that are known to be false. The fact that these non-corresponding mathematical structures are useful does not show that they fit the world in the way the realist needs them to. (There are other reasons one could give if they so desired, like mathematical fictionalism)

3:

Natural Kinds

With these realist defenses answered, another prominent realist stronghold would be an appeal to Natural Kinds. The "natural kinds" defense. The world is objectively "carved at its joints," and our successful scientific theories are successful precisely because their classification schemes have latched onto these pre-existing "natural kinds" this defense rests on an assumption called “coordination” whereby scientific kinds must coordinate with natural kinds. In the interest of trying to keep as much brevity as I can, I won’t go through prebuttals of this position, but it would largely rely on things like essentialism and other things which there is a good amount of literature on

Wait a moment though, what does that mean? To “carve nature/the world at its joints” to put it simply, it’s that there are objectively real divisions in the world, and our concepts or classifications should track those divisions. So: to “carve nature at the joints” means to form categories that reflect the real structure of reality,

I will briefly note however that there has been a particular attempt to save realism using natural kinds from realists like Boyd who liberalized the concept into Homeostatic Property Clusters (HPC). Yet this liberal realist view already is a form of perspectivism. Boyd’s view explicitly makes kinds relative to "disciplinary matrices" and "human projects" Which seems to raise a question that if standard realism already accepts that kinds are mind-dependent, interest-relative, and perspectival, what new contribution does "perspectivism" make?

Perspectivism's contribution comes from answering a different procedural question: "How do scientific theories carve up the world?" Insofar as science does not discover kinds (essences or clusters); it constructs them. So, science constructs "theoretical kinds" through its models. This account provides the definitive solution to the "Failure of Fit" argument and, in doing so, I think it provides the resources to defeat the "Escape” from perspective. The traditional realist picture from natural kinds assumes a:

"First kinds, then laws, then theories" structure.

On this view, scientists first identify kinds in the world and then discover the laws that govern them (Contra TVAR). Perspectivism, as developed here, inverts this. The process is

"First theories, then laws, then kinds."

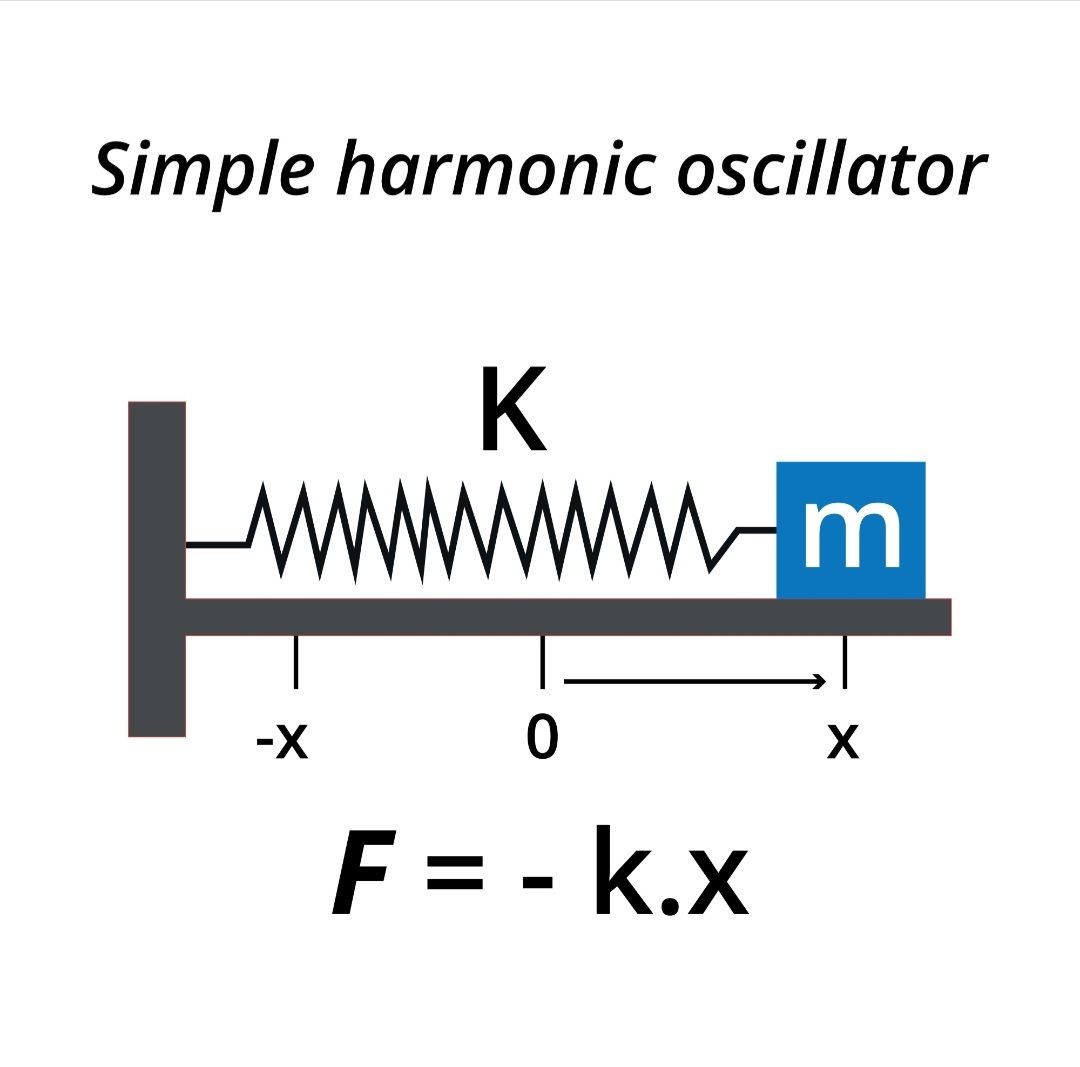

Theoretical kinds are defined by the models themselves. The principles of a theory (e.g., Newton's laws) are used to construct abstract, idealized models (e.g., the simple harmonic oscillator), this model defines the theoretical kind "simple harmonic oscillator". This kind, being an idealization, is not perfectly instantiated in the world. A real-world object (like a pendulum) is only identified as being a member of this kind insofar as it is judged to be similar to the abstract model, in specific respects and to a specific degree. Crucially, this judgment of similarity is interest-relative.

In theoretical perspectivism, the role of interests and purposes are constructive. Because no theoretical kind is ever perfectly instantiated, our purposes determine the very existence of the kind's empirical counterparts by setting the standards of similarity. The kind "pendulum" (as an empirical, not abstract, category) is actively constructed by our decision to treat certain real objects as if they were simple harmonic oscillators, to a degree of precision that satisfies our purposes.

In which there are three primary "constructive practices" that create theoretical kinds by imposing a conceptual framework onto the world.

Idealizations (This is bracketed, as idealizations are often known falsehoods, like "frictionless plane," and thus are not candidates for natural kinds, which are the realist's target)

Schematic objects. A schematic object is an abstract entity in a high-level theory or principle that has no general, fixed definition. It is a conceptual "placeholder" or "empty role" that must be "filled in" by a more specific model.

E.g. "Population" in Evolution. The abstract principle of natural selection (D), "If a is better adapted than b in environment E...", refers to a "population" from which a and b are drawn. But "population" is a schematic object. To make this principle a testable, specific model (Di), such as one about moths, a biologist must choose a specific, concrete definition of "population" (e.g., a specific geographic boundary, a specific species concept). This choice is a pragmatic, perspectival act of construction.

Boundary Construction, which is the imposition of discrete boundaries onto a world that is, in many respects, continuous.

Thus, such an account abandons coordination. As the goal of science is not to make its "theoretical kinds" coordinate with the "natural kinds" of the world. The theoretical kinds are the kinds of science, and they are successful without perfectly "fitting" any pre-existing lexicon of the world.

So, with ALL of that said, in concerns to "Escape" arguments which is that any perspectival fact P (e.g., "The sky is blue") can be trivialized by appealing to a higher-level, non-perspectival fact P* (e.g., "The objective facts of optics + the objective facts of the human visual system cause P").

TKP would refute this by showing that P* is also a perspectival fact. Because the description of P* is itself riddled with "theoretical kinds" created by "boundary construction". To state P*, the realist must refer to "the sky," "blue," and a "normal human trichromat." But, "The sky" is a vague boundary drawn onto a continuous atmosphere. "Blue" is a "chunk" imposed on a continuous spectrum of light. "Normal human trichromat" is a "chunk" imposed on a continuous variation of human visual capacities. The "non-perspectival" fact P* is just as perspectival as the fact P it was supposed to ground. The "Escape" fails because all facts are perspectival. It is "perspectives all the way down".

Furthermore, the realist (like Button) claims that to describe two rival perspectives (e.g., of Putnam's world), one must presuppose a shared, "behind-the-schemes," non-perspectival description (e.g., "there are three atoms"). But the response here, need only be that this confuses using a perspective with describing one. When I describe P1 and P2, I am simply using a third perspective, P3 (e.g., the "atom" perspective), to do so. My description from within P3 is not "non-perspectival"; its own perspectival nature is simply unstated while I am using it.

So this TKP would grant us that facts are products of interaction. Facts (true propositions) are the product of the interaction between the mind-independent world and our constructed classificatory schemes.

Claims within a perspective can be true or false and TKP is compatible with standard theories of truth (correspondence, coherence, pragmatist), as long as they are understood to operate within the boundaries of a given perspective.

Perspectives are partial and it is only by partially focusing (e.g., selecting a scale) that discrete theoretical kinds (like species) can be constructed at all.

Different perspectives may both be accurate. Perspectives are also evaluated by purposes. Purposes are constructive. Our goals and interests are essential in building the theoretical kinds (e.g., by setting boundaries and similarity standards) that, in turn, constitute the facts of our world and finally TKP successfully track mind-independent regularities in the world (Yes, yes I can feel the self-defeating objection waiting to be raised, just hold on though).

There are many senses of mind-independence. The relevant sense in this context, where we are claiming that perspectives track mind-independent features of the world, is location. That is, an object or event is mind-independent just in case it occurs outside of the mind. A fact that is itself asserted from within our own scientific perspective that distinguishes between minds and the external world. Consider Kitcher’s thoughts on this:

“Central to our ordinary explanation of what the subject does is the idea that she represents objects that would exist even if she were not present. We take the dots on the map as corresponding to things we can pick out in her environment (underground stations), and we think that the associated items in her mental state also correspond to those things.” (2001: 181)

We observe other people (like Kitcher's map-user) and, from our perspective, we explain their behavior by positing a difference between their "mental representations" and the "external objects" they track. We then generalize this highly successful explanatory model to ourselves, positing that we, too, are subjects interacting with a mind-independent world .

Therefore, the proposition "a mind-independent world exists" is not an exception to perspectivism or relativism; it may very well be called an axiom of our perspective. Its truth is relative to this entire scientific framework. Further note that this does not need to turn on a Kantian-style framework that the thesis explicitly rejects whereby we must equate "perspectival" with "appearance" (phenomena) and "non-perspectival" with "actual" (noumena). This is a false dichotomy.

The perspectivism developed here is not an idealism that denies the "actual" world in favor of "appearances." It is more accurately an interactionist model that argues the only "actual" world we can ever know, describe, and operate within is the one that is co-constituted by the interaction between our conceptual schemes and the mind-independent world.

I actually think the "appearance" thing is a problem for the realist as the traditional realist must posit a "world-in-itself" (the "actual" one, which is "lexicon-dependent" and carved "at its joints"). However, since all our access is mediated by theories, the realist can never know if their theories have successfully "fit" or "corresponded" to this hidden, "actual" world. They are forever separated from their "actual" world by a "veil of appearance" (i.e., their models).

Relativists reject this hidden, "actual," pre-structured world. The "Failure of Fit" argument is precisely against it. The perspectivist can be considered a direct realist, but they are a direct realist about perspectival facts. Such that the world constituted by our successful practices is the actual world. Recall the relativist locates structure in our constructed perspectives (our "theoretical kinds," "boundary constructions," and "schematic objects"). The world constrains our perspectives, it provides the "volitionally impenetrable" as Hudson calls it, feedback that makes some perspectives useful and others (like a flat-earth theory) fail. But it does not provide the classification scheme itself. The realist must believe the regularity "F=ma" is in nature; whilst the relativist argues "Force," "mass," and "acceleration" are our constructed concepts that successfully track mind-independent regularities. Now this part was largely about sciences and alethic relativism but with that general idea in play we can extend this to other domains and obtain a nice framework for relativism:

(1) Any statement about the world will involve some lexicon or classification scheme. There is no good way of making sense of the idea that such classification schemes "carve nature's joints", as it were. Truth is relative to the schemes that we construct.

(2) There's a top-down argument that begins with the question of what exactly truth is. The most plausible versions of most theories of truth entail relativism.

(3) "Put up or (nicely) shut up": If you think that there are absolute truths, tell the relativist what they are. The best candidates will all turn out to be dependent on particular perspectives.

Responses to objections

The long-awaited section of this article, we will proceed without further ado

Relativism is self-defeating:

(a): What about the statement that “all truths are relative” is that not an absolute statement?

The relativist is simply going to hold that the statement is only relatively true, that is, it expresses a truth from within the relativist framework

(b): If relativism is only relatively true then that means it can be relatively false and therefore contradicts itself

Relativism is not subjectivism, plus all that goes to show is the relativists point, that is no perspective-independent truth. The relativist can argue that relativism is true from your perspective as well (See the next objection/point as that ties into this)

(c): If absolutism is relatively true then that also refutes relativism

The objection here would be that this is only a problem if one assumes an absolutist account of truth, as the relativist does not hold to the contradiction that relativism is true and false

(d): Hales’ objection: in the positions where relativism is relatively false it would be false simpliciter

That is putting his argument simply but, it is that when a relativist admits that an Absolutist exists and holds an Absolutist belief, the Relativist must concede that Absolutism is "true simpliciter." Because relativism is false in that perspective because the content of the Absolutist's belief is 'universal,' the truth-value of that belief must be universal. To which it will just be said that the fact that the Absolutist's framework contains a 'universality clause' does not make their framework the universal “law of reality” or something akin to that. It just makes it a framework that claims to be universal. The relativist explains this claim as a feature of that specific perspective, unless you believe it is a feature of reality itself or something akin to that

To lean on Baker: "The self-refutation objection assumes either Belief... or Plenitude (for every proposition, there is some perspective from which that proposition is true):... that there is some perspective from which absolutism is true.” Hales assumes that because one can conceive of an Absolutist perspective, that perspective must be valid which assumes that the "Absolutist Perspective" successfully generates a truth insofar as it assume that for the proposition "Relativism is False," there must be a perspective that makes it true. But again a relativist does not have to accept Plenitude. The response only need be that the absolutist believes their box is universal. But their box is just a local perspective with a delusion of grandeur for lack of a better word. The proposition 'Relativism is False' is not true, even relative to them. It is just a false belief they hold/them being mistaken about their position.

Correspondence and empirical truths:

Now this is a response I think is just as common, and I honestly take it that these two things are the same refutation whereby empirical claims correspond to the world. But the relativist would just hold that correspondence only makes sense given relativism. Correspondence claims that P is true just in case P corresponds to the facts. i.e. P bears a special kind of "matching" relation to the facts. But what is this matching relation supposed to be? According to a relativist, a person compares what they take to be the proposition with what they take to be some aspect of the world, and they judge that they share the relevant features, where what counts as the relevant features is determined by the framework in question. Which was talked about extensively above given perspectivism so I will focus on problems with correspondence itself

We have already talked about in length that the traditional correspondence theory posits that a proposition P is true if it corresponds to a fact F in the world but for this relation to hold objectively (without relativism), the world itself must be "lexicon-dependent". Such that for the human statement "The cat is on the mat" to correspond to the world intrinsically, the world must come pre-packaged with the distinct, objective categories "cat," "mat," and the relation "on." The world does not possess a "lexicon" or a "language". The idea that the world has a pre-existing conceptual structure is a "theological relic". Because the world is “unstructured” and complex, while our representations are structured and partial, there is a fundamental "mismatch" or "failure of fit" between our concepts and the world. Therefore, "correspondence" on its own is metaphysically impossible because one side of the equation (the world's "language") is missing

What exactly it could be for a proposition to match the world, independently of anybody's judgment about it, is much more obscure and queer. However, another serious problem for traditional correspondence theory is that there are a variety of relations that propositions can bear to the facts. So if P bears a truth-making relation to the facts, then ~P must bear a falsity-making relation to the facts. If I can map P to the facts, I must be able to map ~P to the facts (because I can ~P to P via the negation function). This is actually quite a popular problem with correspondence (and more generally using states of affairs which much can be said on– so much so in fact that I am going to choose to keep it brief for the paper), now the correspondence theorist might reject negative facts. Then maybe “Not-P” is true because P fails to correspond to a fact.

“It’s true that snow is not white” because “snow is white” fails to correspond to any state of affairs.

Even though this seems fairly intuitive, in this case the theory stops explaining truth and starts explaining falsity. It defines truth in terms of non-correspondence and this is circular, since we’re trying to say what truth is, not what falsehood is. Besides this is only more credence boosting for relativism as relativism supplies the “cut-off” (e.g. where things end and begin)

Even worse: this makes the truth of “Not-P” depend on the absence of a fact corresponding to P, which is not itself a correspondence relation. The world doesn’t positively contain “non-whiteness of snow” it simply lacks “whiteness of snow.” So correspondence becomes asymmetric.

Furthermore, as it were, correspondence would face the “slingshot” problem (for the sake of brevity, see the SEP on this)

Other truth theories?

It can be argued relatively easily (See what I did there?) that all other truth theories mesh into relativism very well (deflationism, coherence, etc). Furthermore, any candidate truth that may be given by an opponent can be shown to be dependent on a particular perspective

Mathematical and logical truths?

It’s the same jazz here, recall that the relativists hold that there are no truths that are true independently of any perspective (framework, schemes, etc.). I think there is a plausible case for fictionalism about mathematics, and on such views, all mathematical statements are false and this would also line up with the fact mathematics cannot apply to the world directly; it requires a prior, non-mathematical layer of interpretation that is inherently perspectival as a mathematical structure (sets of objects and relations) is abstract and says nothing about the world on its own. I am not a fictionalist, but I do think that we construct objects such as numbers through some process of abstraction. Whether there are mathematical objects, so whether terms such as "1" refer, will be dependent on one's linguistic framework as well as a model-theoritic relativity (e.g. 1 + 1 = 2). Remember all statements about the world or anything else begin with some lexicon or scheme according to the relativist. With logical truths it is relatively the same, we already notice plurality within logic (e.g. free logic, paraconsistent, etc.)

For now, though we will just focus on classical logic and once we see relativity there it should be easier to see relativity for logic in general. In any case a structural view of logic is most plausible, logical truths are schematic objects (see the natural kinds section) and as such they are empty forms. This is not particularly controversial; it is standardly held that logic is content/domain neutral such that it abstracts away from the content of its propositions. Consider:

All X are Y

Z is an X

Therefore, Z is Y

This works identically whether we're discussing:

Philosophers (All Greeks are mortal / Socrates is Greek / Therefore Socrates is mortal)

Chemistry (All acids have pH < 7 / Hydrochloric acid is an acid / Therefore it has pH < 7)

Fiction (All unicorns have horns / Sparkle is a unicorn / Therefore Sparkle has horns)

Or say we had a tautology “Mars is dry or not dry” (P v -P) the statement would compute as true even if “Mars” referred to my bottle of cologne and “dry” referred to the property of being a prime number. The statement would be true under all interpretations of the logical and non-logical terms.

Given that they are neutral with respect to the world this spells out good news for the relativist as they can similarly say that logical schemata (the so-called logical vocabulary that is kept fixed within systems of representation like language) e.g. connectives as well as operators like “and”, “or”, “not”, etc. Are similarly dependent on linguistic frameworks (alas it is standard to hold semantic-constitutive views of logic anyway). This can be extended to concepts like the truth-functionality of logic where the truth of complex statements are determined by the truths of their parts in classical logic (e.g. P ∧ Q, “Grass is green AND the sky is blue” is true if and only if grass is in fact green and the sky is in fact blue) which would just lead us back to the relativism-correspondence dialogue and other schemata like tautologies whose truth-functional combinations guarantee truth in all circumstances would be based on these linguistic-semantic frameworks because logical truth is merely the result of logical schemata (the fixed vocabulary of 'and', 'or', 'not'), then logical truth is dependent on the representational framework that defines those connectives and we define the connectives via their truth tables or inference rules. For example, It's a law of logic (De Morgan’s law) that any instance of the schema [~(p v q) <-> (~p & ~q)] is true. What grounds this fact is the truth functions denoted by '~', 'v', '&', and '<->'. Functions which we conceptually denote.

Much more can be said about logic as well as formal languages with respect to relativism but I will leave it at that for now. Crucially, as is the case with different systems of logic, validity (which is a chief concern of logic) is relative to the system. An inference is not "valid" simpliciter; it is only valid in virtue of a specific set of rules. Also see Gillian Russel’s logical nihilism which makes a good case against a traditional monist conception of there being laws of logic here

Conclusion

And so we have it, the end of our long and extensive article on truth relativism. Hopefully it is something you found yourself enjoying despite its length and subject of a seemingly absurd philosophical concept. However if you do still find yourself having grievances and uttering that relativism is completely false… well that's true for you but not for me!